Base Ball in Brooklyn, 1845 to 1870

by David Dyte

An edited and footnoted form of this essay appeared in the journal Base Ball in

Spring, 2012. The same version was also

reproduced

in John Thorn's Our Game blog.

Late in the 19th century, the Brooklyn Eagle took

an interest in the local history, and printed colorful stories of all manner of

leisure pursuits from the youth of prominent members of Brooklyn society. Some

of these accounts gave clues as to the early popularity of base ball among the

boys of the area. Former Mayor Frank Stryker wrote:

I went to school in

1820-1, to one Samuel Seabury, on Hicks street, near Poplar, and afterward in a

private house at the corner of James and Front streets; then to one Lummiss,

who taught in the Titus House, in Fulton street, between York and Front. I also

attended Mr. Hunt's school, over George Smith's wheelwright shop in Fulton

street, opposite High. Foot racing and base ball used to be favorite games in

those days, and we used to go skating on Fricke's Mill Pond, at about Butler

street and Third avenue.

Colonel John Oakey had taken his schooling at Erasmus Hall in

Flatbush from 1837, and provided this tale:

Erasmus Hall academy

had a fine play ground surrounding it. Here John Oakey and his school fellows

played many a game of three base ball. The boys who played were called binders,

pitchers, catchers, and outers, and in order to put a boy out it was necessary

to strike him with the ball. On one occasion John Oakey threw the ball from the

second base and put another boy out. The boy said he did not feel the ball and

therefore he had not been put out. John made up his mind that the next time he

caught that chap between the bases he would not say afterward that he did not

feel the ball. It was only a few days after that an opportunity occurred. John

let the ball go for all he was worth and caught his boy in the back. He went

down in a heap, but instantly sprang to his feet and cried out, "It didn't

hit me; it didn't hit me." But John Oakey and all the boys knew better.

For a week after that boy had a lame back, but he would never acknowledge that

the ball did it.

On October 13, 1845, the following item appeared in the True

Sun newspaper of New York:

The Base Ball match

between eight Brooklyn players, and eight players of New York, came off on

Friday [October 10] on the grounds of the Union Star Cricket Club. The Yorkers were singularly unfortunate

in scoring but one run in their three innings. Brooklyn scored 22 and of course came off winners. After this game had been decided, a

match at single wicket cricket came off between two members of the Union Star

Club - Foster and Boyd. Foster scored 11 the first and 1 the second innings. Boyd came off victor

by scoring 16 the first innings.

This short account, lacking any of the dramatic flair later

brought to base ball writing by the likes of Henry Chadwick, represents the

earliest record of an organized base ball game in Brooklyn. The result points

to a game by the Knickerbocker Club's rules, which called for a winning score

of 21 runs. The Union Star Club's grounds

stood opposite Sharp's Hotel, which was at the corner of Myrtle and Portland

Avenues - the present location of Fort Greene Park.

Base ball returned to the Union Star Grounds on October 24,

when the New York Base Ball Club visited. Having defeated the Brooklyn players 24

to 4 in Hoboken three days before, the New Yorkers repeated the feat, taking a

37 to 19 victory in four innings. While it is unclear if the New York Club is the same group of

"players of New York" that played on October 10, the great difference in the

scores appears to indicate otherwise. The New York Morning News said of the Hoboken match:

The fielding of the

Brooklyn players was, for the most part, beautiful, but they were evidently not

so well practiced in the game as their opponents.

Surely this would not have been true of a team that won so

convincingly just eleven days earlier.

While the Union Star Club continued to play cricket, records

of organized base ball in Brooklyn disappear between these matches and the

emergence in 1854 of the Excelsior Club of South Brooklyn, a base ball team

organized by the members of the Jolly Bachelors social club. With the founding in 1855 of the

Eckford Club of Greenpoint, and the Atlantic Club of Bedford, Brooklyn's

triumvirate of great base ball clubs was complete. Pushed hard by many other

local clubs such as the Putnam, Enterprise, Star, and Resolute, as well as clubs

from nearby Manhattan and Morrisania, these teams would dominate base ball for

more than a decade as the sport grew to become America's Pastime.

When the National Association of Base Ball Players was

formed in 1857, the explosive growth of the game in Brooklyn was evident. Nine

of the sixteen founding clubs were from Brooklyn: Atlantic, Bedford,

Continental, Eckford, Excelsior, Harmony, Nassau, Olympic, and Putnam. A

combined team of New York players defeated a similar combination from Brooklyn

two games to one in a series in Queens in 1858, but when the Association first

recognized a formal champion in 1859, the Atlantic Club claimed the title,

sporting a record for the year of eleven wins against just one loss.

Over the next few years, Brooklyn teams would monopolize

competition for the championship, which was passed along by defeating the

incumbent champion across a series of three matches. In 1860, the Excelsiors,

having poached the devestating pitching ability of young James Creighton from

the Star Club, bid strongly to wrest the title from the Atlantics. On July 19,

1860, the Excelsior Club hosted the Atlantic and took its signal victory in the

first game of the series, 28 to 4. The Brooklyn Eagle described the spectacle

the following day:

For a month or more

the Base Ball public has been alive with interest concerning this great

match. At an early hour the crowd

commenced congregating, and when the game commenced there could not have been

less than five or six thousand persons present. The greatest excitement prevailed, and betting stood at 10

to 8 on the Atlantic Club. The

Atlantics were not up to their usual play in any one point, missing balls on

the fly and bound, overthrowing and misbatting. The result of the game was an entire disappointment to the

large crowd in attendance, judging from their moving away like a solemn funeral

procession after the game was over.

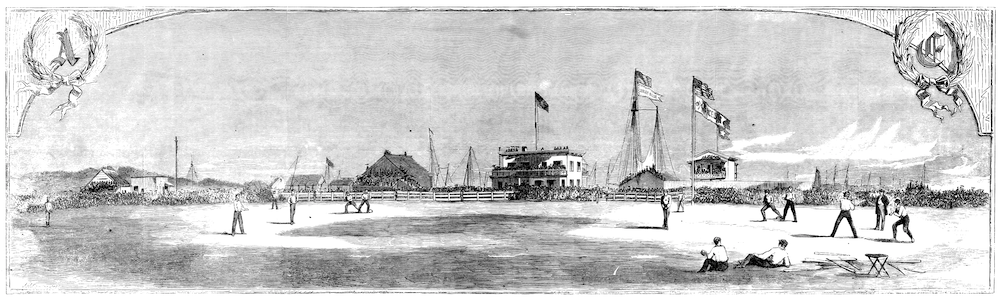

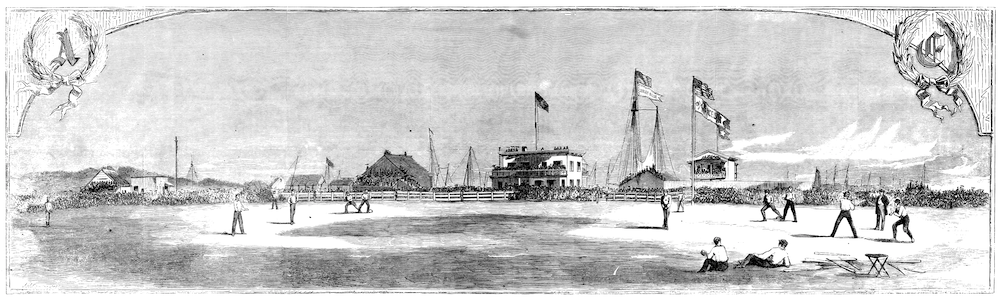

The Excelsior Club hosts, and thrashes, the Atlantic in 1860

On August 9, the Atlantic turned the tables at their own

ground, scoring nine runs in the seventh inning and holding on for a 15 to 14

victory. The Eagle was again

enthusiastic in its description of the scene:

From one to three

o'clock, yesterday afternoon, the avenues leading to the Atlantic ball ground,

at Bedford, were thronged with pedestrians, en route to witness the great

match at base ball that was to take place between

these two clubs, who have no superiors in the country ; and during that time it

was a difficult matter to obtain standing room on either the Myrtle or Fulton

avenue cars, so crowded were they with persons eager to witness the great

contest.

The crowd was far more pleased with the result on this

occasion:

The shout that rent

the air from the stentorian lungs of the countless friends of the gallant

Atlantics was terrific, and it was with difficulty that they made their way to

the club house, so eager were all to congratulate them on such a victory as

they had so manfully achieved.

Thus ended the second

grand ball match of the season, which has proved to be the best contested game

of ball ever played in this country, and certainly the most numerously

attended.

With that paragraph, a minor tradition began, whereby the

Brooklyn Eagle would claim that a local match, generally involving the Atlantic

Club, was the finest yet played. We shall see more of this later.

Despite all this excellent news of the popularity of the

game, and the enthusiasm of the spectators, the concluding match of the series at

the Putnam Grounds on August 23 was to be a disaster. With the Excelsior Club

leading 8 to 6 in the sixth inning, the unruly, abusive behavior of the crowd,

which again had a decidedly pro-Atlantic tone, became so bad that Excelsior

captain Leggett took his team from the field. With the game called off, the

Atlantic Club retained the championship, in fact if not in spirit. The Eagle

left no doubt as to the cause of the bad behavior:

We hope it will be the

last great match that takes place, if such scenes as took place yesterday are

to result from them. Such

confusion and disorder, and such gross interference with a match by the

spectators, we never witnessed. If

the admirers of this manly pastime desire its future welfare, they should at

once proceed to adopt stringent rules among the various clubs, against

betting on the result of the matches played,

for it was unquestionably a regard for their pockets alone that led the

majority of those perculiarly interested in the affair, to act in the

blackguard manner they did.

The Atlantic and Excelsior Clubs would never play each other

again.

While the country was divided by the Civil War, and clubs

such as the Continental were forced to temporarily disband, base ball continued

to be a focus of popular attention in Brooklyn. In 1862, William Cammeyer set out to convert his skating pond

in Williamsburgh for summer sports, and created the Union Base Ball and Cricket

Grounds, the first enclosed base ball park. Rather than charging his tenants

rent, as had the owners of other fields, he let them play for free and took ten

cents from each spectator as the price of admission instead. Cammeyer's economic model soon inspired

Messrs. Weed and Decker, whose Capitoline Skating Club performed the same trick

to create the Capitoline Grounds at Bedford in 1864. A long tradition of ballpark construction for profit, still

very much in vogue today, had begun.

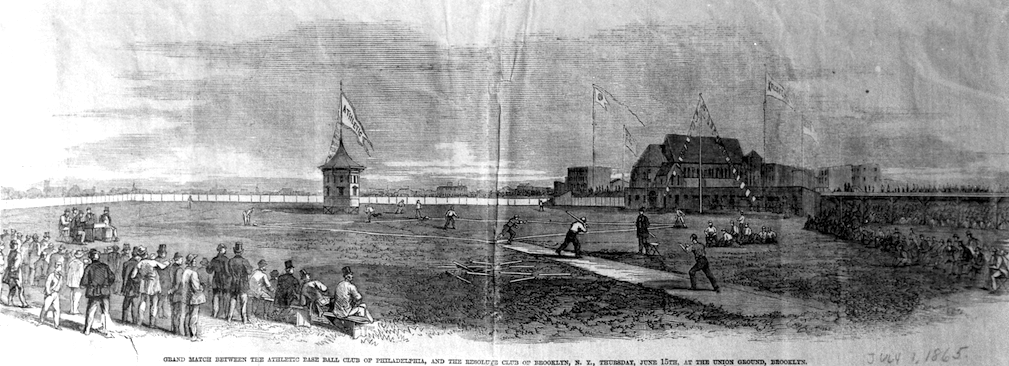

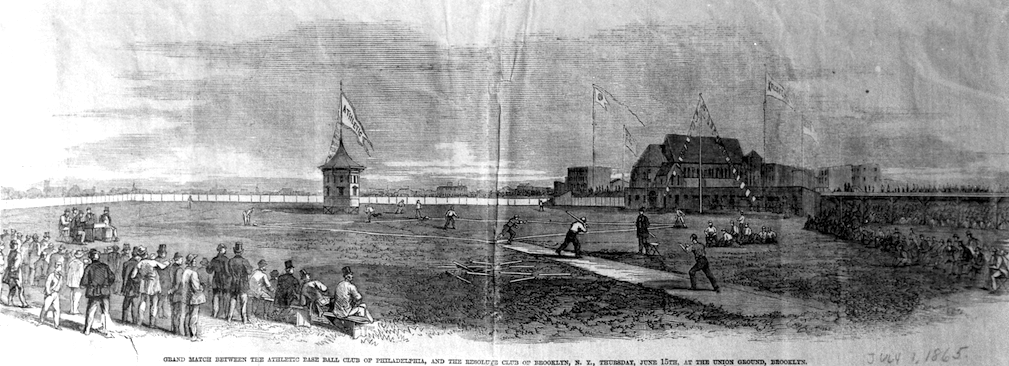

Resolute of Brooklyn vs Athletic of Philadelphia at the Union Grounds in 1865

The Union Grounds proved to be instantly popular, as the Eckford,

Putnam, and Constellation Clubs shifted their homes to the new field. The Eckford Club, a working class

collection of shipbuilders and dock workers, hosted the champion Atlantics for

three matches at the Union Grounds, splitting the first two. The Eagle reported breathlessly on the

decider of September 18:

The deciding game was

played yesterday, when it came off on the Union Grounds, the occasion

attracting an extremely large assemblage of the admirers and emulators of the

game, many being present from other and distant cities. The Nines, of course,

were the most powerful either club could present, and a word in their favor is,

therefore, unnecessary. The grounds, and the sheds and benches erected thereon,

were crowded to repletion, and the embankments outside the enclosure also had

its crowd. As usual, the best of order was maintained, the police being in

attendance. The ground was in fine order, and the game was played with the

spirit that the exercise infuses into the participator. The importance of this

match can be readily realized, since a defeat to the Atlantics would virtually

rob them of the championship, they have so long and nobly sustained, while a

reverse of the Eckfords would be another evidence of the uncertainty and skill

of the game. The contest was witnessed with the most feverish anxiety, and the

air was frequently rent with cheers.

On this, the finest day of the Eckford Club, they took the

championship with an 8 to 3 victory. While the matter settled on the field was becoming ever more serious, however,

its social roots remained in place:

After the players had

doffed their uniforms, the clubs and a few invited guests were the recipients

of a bountiful collation, and as the delicacies under which the laden boards

groaned disappeared the vanquished wore off the keen edge of defeat in social

festivity with the victors.

At the same time, the game itself was constantly

evolving. Henry Chadwick, a

Brooklyn resident whose enthusiastic base ball writing and record keeping

became the stuff of legend, organized regular prize matches at the beginning of

each season. These matches,

involving picked nines of players from various teams, would often trial new

rules, and proved valuable for practice. Not everyone in the increasingly contentious sport agreed, however, and

on May 21, 1864 Chadwick took to print in the Brooklyn Eagle to voice his

displeasure:

Unfortunately there

are too many individuals in the ball playing community who never can see

anything in its proper light that is not immediately connected with their own

pet club, and it is this over-jealous and selfish minority who are the chief

promoters of all the jealousy and ill-feeling that exists between members of

rival organizations. They are

never pleased to see anything done, or hear of anything said, calculated to

benefit any club but their own, and hence their opposition to just such

arrangements as lead to games similar to the Prize Match on the Star Grounds,

which takes place to-day.

Occasionally

the good of the game and the good of the powerful clubs coincided. The fly rule, which was exhibited in

prize matches in Brooklyn in 1864, and had been a feature of regular games

involving the Excelsior and Star Clubs as far back as 1859, was adopted for

general use by the eighth annual convention of the National Association of Base

Ball Players in December, 1864. This rule, preventing a hitter being put out by a catch on one bound in

fair territory, was arguably the most important single change to the game in

its history, and placed the "muffin clubs" at a decided disadvantage against

the better fielding teams.

The Atlantic Club regained its title from the Eckford in

1864, and dominated all comers over the 1864 and 1865 seasons, going undefeated

through both years. Challenges

began to come from further afield. A visit to Boston and a game on September 27, 1865 against the

Tri-Mountain Club on Boston Common seemed to cement the dominance of the

champions from Bedford – the Atlantics scored 68 runs in the last two

innings to cap a 107 to 16 win. To

the south, however, the Athletic Club in Philadelphia was making noise. Spreading word around that the Atlantic

Club would not face them, the Athletics gained a good deal of press for their

views, and proposed to claim the championship by forfeit. The Atlantics, determined not to play

after suffering the untimely death of one time star pitcher Matty O'Brien, were

finally goaded into visiting Philadelphia on October 30. The Eagle was once

again present, and reported a huge attendance at the Athletic Grounds:

The scene at the

grounds was worth beholding. Within the enclosure, the vast crowd formed a large cordon around the

entire circle, to such an extent as to interfere with the fielding at

times. Outside the grounds, the

entire space as far as the eye could reach, was one dense mass of human

beings, all intent on seeing this great encounter. Barouches, buggies, phaetons, and vehicles of every

description filled up the intervening space. The grand stand within the grounds, was filled with well

dressed and good looking ladies, there being not less than 15,000 spectators

present.

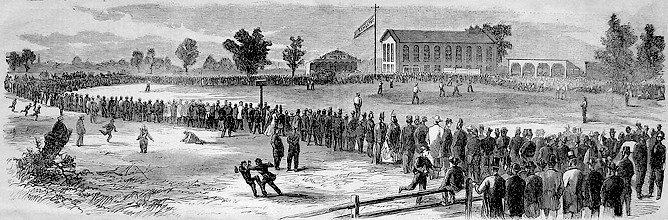

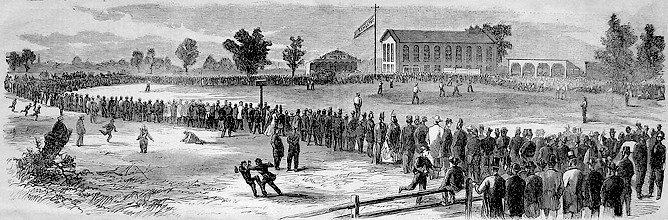

The contentious 1865 match in Philadelphia between the Atlantic Club and the Athletics of that city

The Philadelphians would be disappointed, however, as the

Atlantic Club finished strongly to win, 21 to 15. A week later, at the Capitoline Grounds, the Atlantic

withstood a late comeback from their foes, and won 27 to 24 to retain the

championship. But the rest of the

base ball world was catching up.

The next few years in Brooklyn base ball were a story of

gradual decay at the top level. While junior clubs continued to thrive, especially when the new Parade

Ground was opened for play, the best players at the top teams bickered over

money shared from gate receipts, or left the city completely. The Atlantic Club remained strong,

although no longer unbeatable, and retained the championship in 1866 before

giving the title up to the Union Club of Morrisania (from the Bronx) in 1867. In 1868, the powerful Mutual Club moved

from Hoboken to the Union Grounds in Brooklyn, and claimed the championship

of that year.

It was a club from the west that heralded the bitter end of

Brooklyn's pre-eminence in base ball, however. The Red Stockings of Cincinnati,

largely staffed by players from the New York area, were the first club to be

incorporated as a for-profit business, and the first to openly employ fully

professional players under contract. In 1869, the Red Stockings played all over the country, and won 57 games

while losing none. Their efforts

made a mockery of the championship's challenge system, as the Cincinnati team

never played an opponent at the right time to get a shot at the title. The Atlantic Club, which won 40 of 48

games, losing six and tying two, finished 1869 as official champions for the

seventh and last time, to general derision.

In 1870, the Red Stockings continued to take all before them,

and on June 14, the Capitoline Grounds were packed as the mighty club brought

in an 89 match winning streak to meet the Atlantics, no longer champions but still

the pride of Brooklyn. The Eagle

was, as always, present with superlatives at hand:

The most remarkable

game, in more respects than one, was played upon the Capitoline ground

yesterday between the celebrated old Atlantics and the celebrated young Red

Stockings. Notwithstanding the

energetic protest of the Atlantics, they were compelled to charge fifty cents

admission to the ground, and yet from nine to ten thousand people congregated

there, and in the hot sun, watched with intense interest the progress of the

game. The general impression

previous to the game, was that the Atlantics would lose the game ; none but the

nine knew, however, how hard they were going to play. The Red Stockings were bound to defeat their strongest foes,

and played throughout with the same determination. The result therefore was, that the most stubborn game ever

played, was finished yesterday on the Capitoline ground.

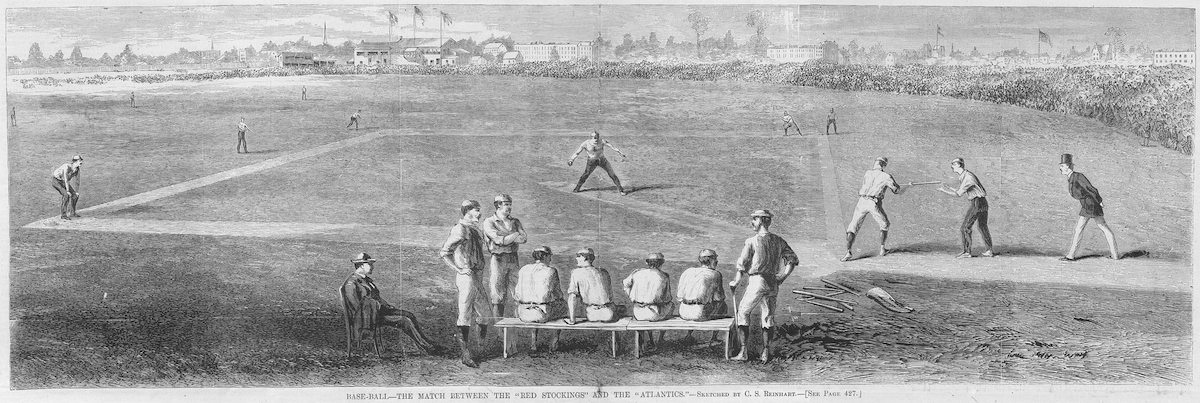

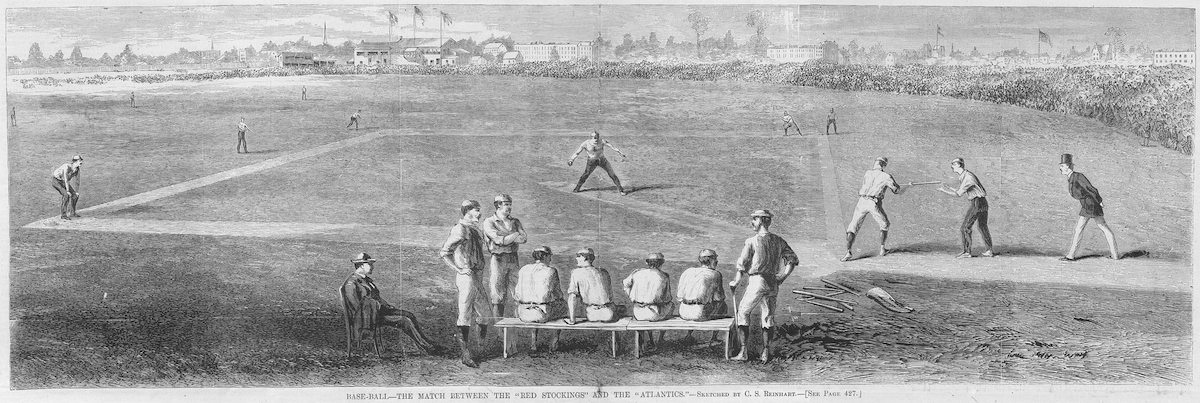

The Atlantics take on the mighty Red Stockings in 1870

History records that the Atlantics, by some miracle, scored

three runs in the eleventh inning to win 8 to 7. As great as this win was, though, even the parochial

Brooklyn Eagle was in two minds about its meaning. One editorial was effusive

in its praise:

Moreover, it was won

by the fairest, staunchest, skillfullest, pluckiest playing on record.

"Science and nerve" did the business. Eleven innings, a total score

of fifteen, and that standing just eight to seven, tell a story to professional

minds which sends the blood tingling in joy to their toes. It was the greatest

game ever played between the greatest clubs that ever played and, as usual,

when Brooklyn is pitted against the universe, the universe is number two.

Another was far more reserved:

We would not rob the

Brooklyn champions of the temporary glory of having beaten these professional

experts. It is possible the game was fairly played throughout and honestly

contested by the Red Stockings, but this defeat coming after a series of almost

unprecedented victories looks much like the old sporting adage of letting up to

win. A great deal of money changed hands yesterday, but we doubt if any of the

regular backers of the Red Stockings were among the losers.

In short, the romance of the organized game in Brooklyn,

optimistically planted in 1845, had been replaced by the same kind of hardened

cynicism that accompanied the end of the 1860 Excelsior-Atlantic series. The

incredible victory over the Red Stockings was the last gasp of the era.

Not much was left for the three great clubs of

Brooklyn. The Excelsior had

already disappeared, and the Atlantic and Eckford Clubs saw their best players

leave for the fully professional life elsewhere when the National Association

opened for business in 1871. Their later entries in that competition were

unsuccessful, to say the least. The Mutual Club remained in Brooklyn long

enough to join the National League in 1876, but lasted no longer. The Dark

Blues of Hartford moved to Brooklyn in 1877, and played only that season. Even

after Charlie Byrne and his associates founded a new Brooklyn Ball Club in

1883, things would never really be the same. Brooklyn was no longer the center of the base ball universe.

BrooklynBallParks.com is brought to you by

Andrew Ross (wonders@brooklynballparks.com)

and David Dyte (tiptops@brooklynballparks.com).

Please contact us with any corrections, additions, or requests.