Brooklyn's Ancient Ball Fields

In the base ball boom of the 1850s and 1860s, and even before that, playing fields appeared all over

what is now modern Brooklyn, from Red Hook to distant Coney Island. Some lasted barely a year, some

for decades. The best remembered are the Union and Capitoline Grounds, of course, but the history is

much deeper than that. We have tried to list the other important early fields here. If you don't see

an ancient field you expect, it is probably on our page of other parks.

Brooklyn Union Star Cricket Club Grounds

Opposite Sharp's Hotel, corner of Myrtle and Portland Avenues, near Fort Greene.

The Union Star Cricket Club was formed in 1844 by Henry and William Russell, formerly of the St. George

Cricket Club of Staten Island. The club was largely Jewish, and in laters years switched games to

base ball.

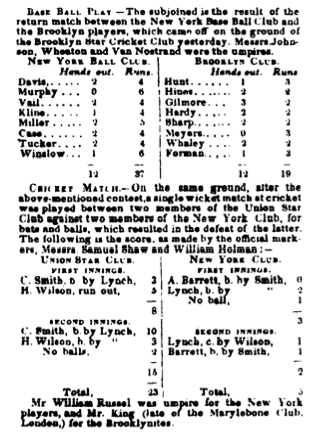

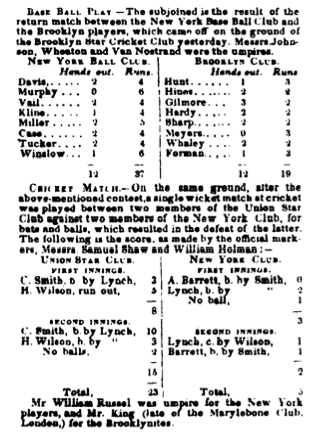

This ground saw the earliest recorded game of organized baseball in Brooklyn - an eight against eight match

between the members of the Brooklyn and New York Clubs on October 10, 1845. The Brooklyns - featuring

four members of the cricket club - won by a score of 22 to 1 in three innings, in a game presumably played

under the 1845 Knickerbocker rules, which called for a winning score of 21 aces. The New Yorkers later

defeated Brooklyn at Hoboken, and again at the Union Star Grounds on October 24. The scorecard of this last

match was provided by the New York Herald the next day. The Brooklyn Club did gain some revenge that day by

handily winning a single wicket cricket match after the base ball game.

New York Herald, October 25, 1845

This field formed part of Fort Greene Park (originally called Washington Park) from

its establishment in 1847, and in 1857 one W.S. Dodson was granted permission by the Common Council

of Brooklyn to play base ball at the park. Like the other Washington Park at 5th Avenue and 3rd Street, this

one was an important site in the Battle of Brooklyn. A column stands atop the hill, the original

site of the Fort, commemorating the Prison Ship Martyrs of the Revolutionary War.

George Brainerd's photograph of football at the park in the 1870s

Photograph courtesy Brooklyn Public

Library—Brooklyn

Collection

Early in the 1900s, the Washington Field Club played matches at the park. On August 28, 1907,

the Brooklyn Royal Giants visited, and were trounced by the Washington F.C., 28 to 9 in front

of 500 spectators. Morton and Ramsdell each scored seven times for the home team. For the Royal

Giants, Berry was pressed into service as a relief pitcher, having caught the early part of the

game, and still found the energy to go 3 for 6 and score two runs.

Baseball and softball continued at Fort Greene Park for some years. In 1915, summer Bible school

students played baseball at the park daily. In 1925, the Inter Park League had regular games

at Fort Greene Park - On August 13, Browne Park crushed City Park, 10 to 1, with pitcher Mankowski

allowing just three hits. In 1926, The Cyrene Athletic Club played a series against the Shawnee

Athletic Club, winning handily. In later years, Brooklyn College and Brooklyn Tech used Fort Greene

Park as a practice field. As late as the 1950s, softball was a regular feature.

Nowadays, however, with trees all over the park, there is scarcely room for any sports, other than at

the tennis courts. There might be room for a baseball game in the southeast corner, where soccer is still

played. This happens despite a ban on ball games - the Parks Department is known to turn a blind eye.

Fort Greene Park today - overhead, the southeast corner,

better suited for a game nowadays, and the northwest,

where the cricket grounds probably once were

Atlantic Ground

Marcy Avenue between Putnam and Gates Avenues, near Wild's Hotel.

This ground was home to the Atlantic Club before moving to the Capitoline Grounds in 1864. This field saw many famous

Atlantic victories during their first hat-trick of championships from 1859 to 1861, including the overwhelming 52 to 27

demolition of the Mutuals on October 16, 1861. Henry Chadwick wrote that the Atlantics played with "all their pristine vigor and excellence." Every

Atlantic player scored at least five runs in the game, and the team tallied an amazing 26 runs in the third inning.

Even when the Atlantics were not champions, matches here proved to be popular. On June 18, 1863, the Athletic Club

of Philadelphia, a regular rival of Brooklyn's best nines, visited for a grand match:

The Atlantic's beautiful ground at Bedford, presented an unusually attractive and gay appearance, yesterday, on

the occasion of a match between them and the Athletics of Philadelphia. An assemblage of some six thousand people; a fair

sprinkling of whom were ladies, formed a semi-circle around the field, which was in excellent order, having been much

improved by the rain on Wednesday. The housetops and trees in vicinity, too, were occupied by crowds of adolescent

humanity, who on such occasions presume to be critics, and pronounce their pleasure or displeasure, in a way that is

very annoying to those near them. The usual extraneous preparations, such as refreshment tents, booths and the like

were erected in various portions of the hustings. Then outside of the crowd was a row of carriages and other vehicles,

they too were filled with eager spectators.

Despite missing pitcher Matty O'Brien, by then confined to bed with the illness that would eventually take his life,

his replacement Al Smith was effective and the Atlantic won by a score of 21 to 13.

The Enterprise Club also shared this ground, and other nines made regular use of the venue after the Atlantics moved, perhaps

not entirely for the good condition of the playing field. An 1864 game between the Atlantic and Eagle muffin nines drew

some attenton from the Brooklyn Eagle:

Those desirous of seeing sport should visit the Atlantic ground to-morrow, and witness the

muffins of the Eagle and Atlantic clubs play. We need not inform our readers that the first nines

of the two clubs will be among the spectators, and that a full delegation of reporters will be on

hand, because both parties are always on hand on these occasions, not of course to partake in the

lager and supper part of proceedings - the idea of such a thing - but simply to give an

account of these important games.

Yukatan Ground

Bedford.

Better known as the Yukatan Pond, this was a public venue for skating every winter in the early 1860s.

On October 16, 1862, a Brooklyn Eagle reporter, probably Henry Chadwick, was sent to the

nearby Atlantic Ground and was amazed by what he witnessed. We have edited this article to remove

some well intentioned racial language quite unacceptable by modern standards:

The return match between the Atlantic and Harlem Clubs did not take place as appointed yesterday

afternoon, but was postponed on account of the unfit condition of the grounds for playing. Among the

large crowd that visited the ground was our reporter, who, on learning that the match would not be

played, went on a perambulating tour though the precincts of Bedford, waiting for something to "turn

up." He had not proceeded far when he discovered a crowd assembled on the grounds in the vicinity of

the Yukatan Skating Pond, and on repairing to the locality, found a match in progress between the Unknown

and Monitor Clubs - both of African descent.

Quite a large assemblage encircled the contestants. Among the assemblage, we noticed a number of

old and well known players, who seemed to enjoy the game more heartily than if they had been the

players themselves. The contestants enjoyed themselves hugely, and to use a common phrase, they

"did the thing genteely." All appeared to have a very jolly time. It would have done Beecher, Greeley,

or any other of the luminaries of the radical wing of the Republican party good to have been

present. The playing was quite spirited, and the fates delivered a victory for the Unknown. The

occasion was the first of a series. We append the score:

UNKNOWN HL. R. MONITOR HL. R.

Pole, 3d b.........3 5 Dudley, 1st b......3 2

V. Thompson, lf....2 7 W. Cook, rf........2 2

Wright, 2d b.......3 3 Williams, ss.......2 1

J. Thompson, p.....5 4 Marshall, 3d b.....4 1

Smith, cf..........0 9 G. Abrams, p.......3 2

Johnson, c.........4 2 Brown, c...........3 3

A. Thompson, 1st b.3 4 Cook, lf...........4 1

Durant, rf.........4 3 Orater, 2d b.......3 2

Harvey, ss.........3 4 J. Abrams, cf......3 1

-- -- -- --

41 15

RUNS MADE IN EACH INNING.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Unknown..3 4 3 7 14 1 1 2 6--41

Monitor..3 3 0 0 2 1 1 5 0--15

Umpire -- C. Ophate, of the Hamilton of Newark.

Scorers -- Baker, Unknown; Jones, Monitor.

This is the first match to our knowledge that has been played in this city between players

of African descent.

Notes: Harlem was still a white farming community in this era, so the intended match with the Atlantic

Club would not have been interracial. Also, the card as printed in the Eagle does not add up

at all correctly, probably due to Chadwick's handwriting, so we have attempted to make up for

compositor's errors by making an educated guess at the original written version.

Long Island Cricket Club Grounds

Terminus of the Fulton Avenue Railroad, Bedford. 1855 maps appear to indicate that the railway terminus was at the corner of Nostrand Avenue

and Fulton Avenue.

This ground was owned by Mr. Holder, and was the very first home of the Atlantic Club, obviously sharing with the

Long Island Cricket Club. On Independence Day in 1856, the Long Island Club hosted and handily won a cricket match with the

Brooklyn Club, reported in the Eagle as a "quite a grand affair" with "refreshments on hand for the comfort and

gratification of the visitors."

Later, the ground was occupied by the Pastime Club, which included

several former members of the Long Island Cricket Club. In 1858, the grounds were described in Porter's

Spirit of the Times:

The locality of the grounds of the Pastime Club are unquestionably the best in Brooklyn.

Ample shade is afforded, and a fine green turf renders the field peculiarly attractive to the

players, and far superior to the dusty grounds of a majority of the clubs.

On August 18, 1859, the visiting Excelsior Club

overran the Pastimes in the late innings to win 20 to 12. Of note in the fifth inning was a triple play made by the Pastimes, which was the

consequence of a mistaken call by umpire Sniffen of the Atlantic Club. In Chadwick's words:

In the fifth innings of the Excelsiors, Leggett being on the second base and C. Whiting on the

first, Polhemus struck a ball which was prettily fielded by Beers [sf] to second base--putting out

C. Whiting--and by Boyd to third base, at which point Leggett would have been fairly put out if Holt

[3d b] had touched him with the ball, but instead of doing so he threw to first base [Carroll] in

order to put out the striker. The Umpire, however, decided Leggett out, forgetting that in

consequence of Whiting being put out, Leggett was not obliged to vacate the second base, and that,

therefore, it was necessary that he should have been touched with the ball.

The Manor House Grounds

Nassau and Driggs Avenues, and Russell and Monitor Streets, or very near there.

Also known as the Eckford Grounds and the Greenpoint Grounds.

The Eckford Club played rent free on this strip of land, then owned by the Backus Estate, before moving

in 1862 to the Union Grounds, where the club achieved its greatest fame. The Satellite Cricket Club

also played on these grounds, occasionally trying their hand at baseball as well as cricket - this

has caused some confusion between this ground and the separate Satellite Ground. The Wayne Club

was another tenant. The Manor House Grounds are probably now McGolrick Park in Greenpoint.

A controversial match between the Wayne Club and the Lexington Club's second nine on October 31, 1857 saw differing reports

submitted to the local papers by each team. In either case, the Wayne Club won, but the bone

of contention was whether the fifth inning should count, having been played in darkness. A member

of the Wayne Club wrote to Porter's Spirit of the Times: They wanted to take advantage of the

darkness, and insisted the fifth innings should be concluded; which conduct (if I may so speak) so

disgusted three of their members, that they resigned at once, and are now members of the Waynes.

The Eckford Club never took the measure of the mighty Atlantic until after moving to the Union Ground,

but they fought some mighty battles at the Manor House Grounds. On July 8, 1859, over 4,000 spectators

saw Atlantic win, 25 to 15. The Eagle was moved to comment: If any argument were necessary to practically

illustrate the growing popularity of the game of Base Ball with the American public, a view of the Greenpoint

grounds yesterday, with its immense assemblage, would convince the most skeptical.

McGolrick Park (then called Winthrop Park) in 1912

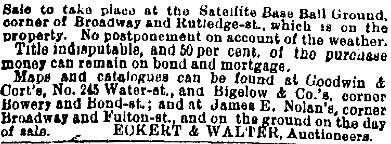

Satellite Ground

Broadway, Harrison Avenue, Rutledge and Lynch Streets.

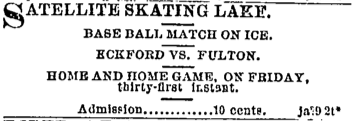

This enclosed ground stood directly across Harrison Avenue from the Union Grounds. The Satellite Ground was home

to the Fulton and Resolute Clubs in 1867, as well as "colored base ball" games including the 1867 championship of

Brooklyn, won 49 to 17 by the Monitors over the Uniques. Also, possibly, the Brooklyn Club around 1860.

Like the Capitoline and Union Grounds, and Washington Park, the Satellite Ground was named after the skating pond on the

same location.

In July, 1867, the Fultons upset the heavily favored Eckfords at the Satellite Ground, by a score of 28 to 20.

The Eagle's reporter marveled at the big hitting of the likes of Fulton's Nasse, who "struck a ball that cleared

the fence on the left of the field, bringing him home." All was not entirely well, however: The managers of the

Satellite grounds should provide decent accomoodations for the scorers and reporters; we saw one member of the

latter class roaming around disconsolately without being able to find a resting place.

In 1867 and 1868, the Satellite Ground fulfilled the function of skating pond and base ball ground,

as a series of matches was on the ice, featuring the squads of the Eckford, Fulton, Empire, and Alaska Clubs.

The ground was sold off for housing later in 1868.

Excelsior Grounds

The foot of Court Street.

Also known as the Star Grounds.

This field was home to the famous Excelsiors from 1859 to 1865. The old club was very strong

for much of this period, regularly scoring 20 or more runs against the finest local clubs, and held quite

a reputation for sportsmanship. As the Eagle declared at the start of the 1863 season: Let the

result be what it may, we know that a fair, square and manly contest will mark every game played on

the Excelsior Grounds.

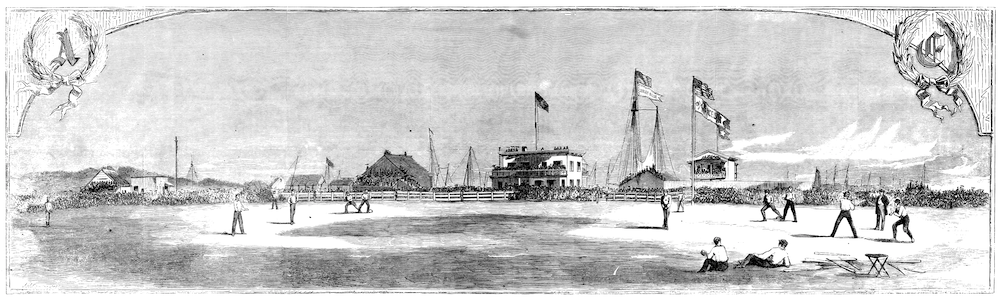

The Excelsior Club scored its signal victory at these grounds on July 19, 1860, over the champion Atlantic

Club in the first game of what became a bitterly contentious three game series. With James Creighton demonstrating

his pitching mastery and the Atlantics uniformly out of sorts, the Excelsiors ran up a 28 to 4 score. A crowd of

"seven or eight thousand persons" witnessed the event, and with odds having been 10 to 8 in favor of the visitors,

much money was apparently lost. Little wonder the spectators left "like a solemn funeral procession."

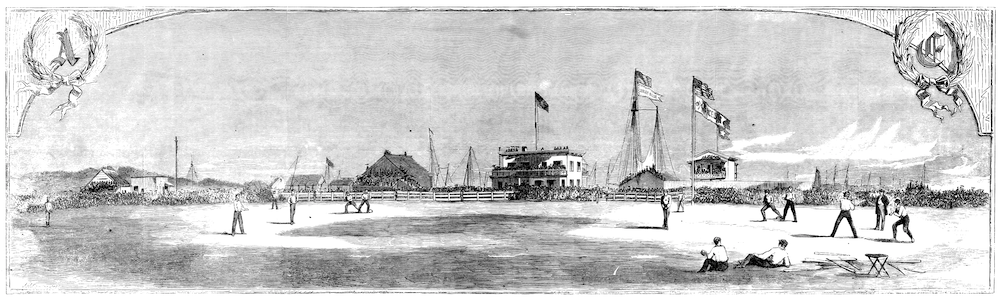

The Excelsior Club hosts, and thrashes, the Atlantic in 1860

In 1864, however, things were not so bright. In a 35 to 19 loss to Newark at the grounds, the

Excelsiors had, by the Eagle's count: over a dozen miscatches, sixteen wild throws from which bases and runs were

secured, nine passed balls in the field ditto and nine behind.

The Star Club shared this ground in 1859 and 1860. Both the Star and Excelsior Clubs were proponents

of the fly game, and played matches under these rules - where catches in fair territory had to be taken

on the fly, not on one bound - at least as early as 1859, six years before the rule was generally in force.

Other matches played here in the 1860s included North Ferries vs South Ferries, and Washington

Hose VI vs. Continental Engine IX.

The grounds are now part of Red Hook Park (or, more formally,

the Red Hook Recreational Area) which contains baseball fields, but the part on Court Street is now

a soccer field.

The Knickerbocker Club of New York and the Excelsior Club of Brooklyn

pose for a photograph at the Excelsior Grounds in August, 1859. The Excelsiors

won the game that day, 20 to 5. This photograph was properly identified in

"Researching the Photograph of the Knickerbockers and Excelsiors" by Tom Shieber

in SABR's Pictorial History Committee Newsletter of June 1999.

Carroll Park Grounds

First field, bounded by Smith, Hoyt, Degraw, and Sackett Streets. Second field,

bounded by Smith, Hoyt, Carroll, and President Streets. Modern park, between President and

Carroll Streets east of Court Street.

One of Brooklyn's oldest parks, Carroll Park was originally created as a community garden in

the 1840s, and acquired by the city in 1856. The Carroll Park Grounds were at times home to

the Excelsior, Star, Marion, Waverly, Alert, Esculapian, Typographical, Independent, and

Charter Oak Clubs. In 1862, a "large and commodious club house" was erected at the

southeastern corner of the site for the use of the Excelsior and Star Clubs. The second field

was also used as a camp for Union Army draftees in 1863.

In 1866, the Typographical nine of Brooklyn defeated the American Bank Note Company nine of New York

64 to 15. For the Typos, pitcher Bergen was presented with a prize bat for scoring 9 runs and making

no outs, and center fielder Henry Chadwick scored 5 runs for as many hands lost.

Over time, Carroll Park was reduced by urbanization and reverted to a more restful area, although

sporting facilities were again added in the 1960s. A 1994 renovation cost $1.3 million and saw

preservation of many of the park's historic touches, and a complete rebuilding of the sports areas.

Carroll Park's sole remaining ballfield, of painted asphalt, is named for Louis Valentino, Jr., a local firefighter

who died in the line of duty in 1996. Valentino was also a star for some years on the Fire Department softball

team. Valentino Ballfield is very unusual in that its lines are not at right angles.

Carroll Park and its strange angles

Overhead picture

taken from Google Maps

Continental Grounds

Lee and Bedford Avenues, Ross and Hewes Streets.

Also known as the Wheat Hill Grounds, and the Putnam Grounds (I).

This was home to the Continental Club, which donated the silver ball won by the Eckford Club when they defeated

the Atlantics in 1862. This trophy had originally been intended for a match between picked nines of

New York and Brooklyn in 1861, but war intervened and the match never took place. The Continentals were great

promoters of the game, unafraid to take on all comers. They were not necessarily great players, however. After

a 21 to 15 loss to the Harmony Club at these grounds in 1856, the Eagle's reporter was moved to write: Bad,

however, as was the play of the Harmony Club, that of the Continentals was infinitely worse - Mr. Brown, the

catcher, being the only good player amongst the whole. They all require a good deal of practice before again

attempting to play a match.

In 1857 the Continentals took on the up and coming Atlantic Club, and were handed a 37 to 21 drubbing. The club

disbanded for a time when members volunteered for the Civil War, and returned afterwards playing at such fields as

the old Atlantic Grounds.

This field was also an early home to the Putnams, who took a fine victory over the Excelsior Club in 1856, 21

to 15 in three innings, after which the teams and their guests adjourned to Trenor's Dancing Academy for

"liberally provided" refreshments. The Resolute and Sylvia Clubs also hosted matches here at

times.

Putnam Grounds (II)

Broadway between Lafayette and Gates Avenues.

Also home to the Constellation Club, the second incarnation of the Harmony Club, and occasionally

the Orientals of Bedford. In July 1860 the Constellations scored a famous home victory over the Nationals,

22 to 18, in a game featuring just one home run and 34 passed balls. The National Club that day featured several

players who would go on to star for the Atlantics and Eckfords. But the ground is far better known as

the site of an infamous match between the Atlantic and Excelsior Clubs, the next month. In the decider of

a dramatic three game series between the clubs, the pro-Atlantic crowd's rowdiness and interference caused Excelsior

captain Leggett, "than whom a fairer, more manly, or more gentlemanly player does not exist," to take his

team from the field, despite them holding an 8 to 6 lead in the fifth inning. The contest was declared a draw

and a much relieved Atlantic Club retained the championship, in fact if not in spirit. The two great clubs

would never meet again on the ball field.

Later that year, the Putnam hosted the Excelsior for a fly game, won handily by the visitors, 23 to 7. The

Eagle's reporter took the opportunity for a close examination of the pitching style of young James Creighton,

then causing a sensation in base ball circles:

The idea of mere speed alone making a swiftly pitched ball a difficult one to hit, by a good striker, is

nonsense to us, as we know that in Massachusetts the balls are thrown very swiftly to the bat, and

they are hit often enough by all. Speed is not the difficulty; it is something else, and that something else

is - as we heard a cricketer remark near the scorer's table, judging the difference between balls coming

straight to the bat and those coming with curved lines. We observed that whenever Creighton pitched his

balls, he delivered them from within a few inches of the ground, and they rose up above the batsman's hip,

and when thus delivered, the result of hitting at the ball is either to miss it or send it high up in the air.

The lower Creighton's balls are struck at the better they can be hit, as he cannot send in a low ball with

that deceptive curve he can a high one.

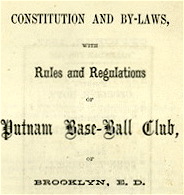

The Putnam Club's constitution was used as the

basis of the NABBP's constitution, in 1857.

Wawayanda Club Grounds

Duck Hill, Coney Island (southeast of Ocean Parkway and Neptune Avenue).

Described in the Eagle as "large and splendid", these grounds saw the Wawayanda Club of Gravesend host the

likes of the Good Intents and the Minawax Club of Flatbush in 1859 and 1860. On October 13, 1860,

the locals defeated Good Intent 33 to 25, in a "spirited match." Every player on the home team scored at

least three runs.

In 1888, the Eagle reported on a game between the Hook and Ladder Company and the Hose Company at the

same grounds. Although the Hose Company could muster only five players, they were made to play:

The Hose Company boys were lazy. They had much rather linger around the stove at headquarters

and listen to Senator Murphy's eloquence, and, beside, there were only five of them and nine of

the other fellows. But the Hook and Ladder nine meant business and said that a failure to play

would subject the Hose boys to unlimited expense for chowder and cigars and froth covered lager

and the latter concluded they had better die fighting.

But a surprise was in store:

From the first the Hose Company began piling up the score and the other nine struggled ineffectually

against fate. John McReady reached out for balls like an officer with a warrant, and fastened them

with the firmness of fate. Counselor Kurth, at first base, stood ready to take anything from a fat fee

to a red hot ball. Constable Kenny Sutherland never missed a ball and the boys said he merely sustained

his reputation.

The five men of the Hose Company took an easy victory in the end, 54 to 11.

George Miller's constant advice, and particularly his help with the location of the Manor House Grounds

deserve our heartfelt thanks. Craig Waff's tireless research into 19th century "protoball" has been a huge source of

new information, also.

BrooklynBallParks.com is brought to you by

Andrew Ross (wonders@brooklynballparks.com)

and David Dyte (tiptops@brooklynballparks.com).

Please contact us with any corrections, additions, or requests.